Locally there was a high degree of concern, especially after the discovery of gold in Victoria, this precious metal was stored in Melbourne awaiting shipment via fast sailing ships to England.

Both the French and Russians were feared as it was believed that they had designs on this GOLDEN HOARD.

As a result, Pinch Gut was built in Sydney as a fort to combat any threat from foreign countries, and Gun batteries were built in Victoria at both Point Nepean and Point Lonsdale to defend the entrance to Port Phillip Bay.

A Doctoral Thesis by Marmion, R. J. (2009). Gibraltar of the south: defending Victoria: an analysis of colonial defence in Victoria, Australia, 1851-1901. PhD thesis, School of Historical Studies, Faculty of Arts, The

University of Melbourne, makes very interesting reading.

From Wikipedia.

Warship Neva arrived in Sydney as part of its circumnavigation of the globe.

Aleksandr Massov

The Visit of the Russian Sloop Neva to Sydney in 1807:

Neva

200 Years of Russian-Australian Contacts

2007 marks the bicentenary of the first contact between Russia and Australia.

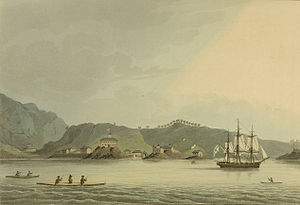

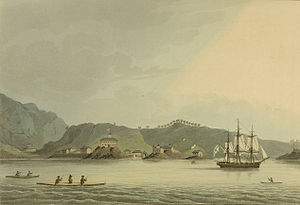

The beginning of relations between the two countries can be dated to June 1807, when the Russian Navy sloop Neva put into Sydney harbour. The vessel was under charter to the Russian-American Company and was bound for the Russian possessions in Alaska with Company cargo. Russian colonization of North America had begun at the end of the eighteenth century and was to continue until the sale of Alaska to the United States in 1867. The

territory was administered by the private Russian-American Company, whose affairs, however, were effectively under direct government control.

The main obstacle to the colonization of Alaska was the problem of maintaining stable lines of supply and of protecting Russian interests in the New World. The overland route from European Russia across Siberia was at that time extremely unreliable, so that the sea lanes remained the only means of supplying Russia.

America and the provisioning and security of the territories were carried out bythe Imperial Navy. For this reason, Russian naval vessels regularly made the voyage from European Russia to Novo-Arkhangelsk, the centre of the Russia's American possessions, throughout the first half of the nineteenth century.

For much of that time, Sydney, and latterly Hobart, were among the few ports of call for Russian sailors as they followed their course from the Indian Ocean to the Pacific; here the crews could enjoy shore leave, repairs could be

carried out, and fresh supplies of water and provisions taken on.

Between 1807 and 1835, fifteen different Russian vessels put in at Australian ports on seventeen separate occasions.

It is therefore hardly surprising that the first Russians Australians came into contact with were seafarers, or that

visits by participants in successive Russian naval expeditions constitute an entire phase in the development of Russian-Australian relations.

The sloop Neva, the first of the Russian vessels to visit Sydney, had some time before taken part with the sloop Nadezhda in the first Russian circumnavigation of the globe conducted under the command of Kruzenshtern and Lisiansky in 1803-06. This expedition, generally successful in achieving its political, scientific and commercial aims, had not included any Australian port of call.

Peter the Great was familiar with New Holland through his connections with the Dutch, and the Empire in the 18th century tried several times, unsuccessfully, to reach the Australian continent.[1]

Contacts between Russia and Australia date back to 1803, when Secretary of State for the Colonies Lord Hobart wrote to Governor of New South Wales Philip Gidley King in relation to the first Russian circumnavigation of the

globe by Adam Johann von Krusenstern and Yuri Lisyansky.[2] As the Russian and British empires were allies in the war against Napoleon, the Russian warship Neva, with Captain Ludwig von Hagemeister at the helm, was able to sail into Port Jackson on 16 June 1807.[3][1] Hagemeister and the ships officers were extended the utmost courtesy by Governor William Bligh, with the Governor inviting the Russians to Government House for dinner and a ball.[4] This was the beginning of personal contacts between Russians and Australians, and Russian ships would continue to visit Australian shores, particularly as a stop on their way to supplying the Empire's North American

colonies. The Suvorov commanded by Captain Mikhail Lazarev (see corrections below) spent twenty-two days in New South Wales in 1814, when it brought news of Napoleon's defeat, and this was followed up by the 1820 visit of the Otkrytiye and

Blagonamerenny. In 1820, Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Vasilyev arrived in New South Wales, on board Antarctic research ships Vostok and Mirny, under the command of Mikhail Lazarev.

Bellingshausen returned to Sydney after discovering Terra Australis, spending the winter at the invitation of Governor Lachlan Macquarie. Macquarie played the greatest role in the expression of Russophilia in the Colony,

ensuring that the Russian visitors were made to feel welcome.[3][5]

Whilst in Sydney, Bellingshausen collected information on the colony, which he published in Russia as Short Notes on the Colony of New South Wales. Within the publication, von Bellingshausen wrote that Schmidt, a naturalist who was attached to the Lazarev expedition, discovered gold near Hartley, making him the first person to discover gold in Australia. While in Sydney, on 27 March 1820, officials from the colony were invited on board the Vostok to celebrate Orthodox Easter, marking the first time that a Russian Orthodox service was held in the Australian Colonies.[3][6]

Although Russia and Britain were allies against Napoleon, the taking of Paris in 1814 by the Imperial Russian Army caused consternation with the British in relation to Tsar Alexander's intention of expanding Russian influence which would compete with Britain's own imperialistic ambitions.

Further visits to the New South Wales colony in 1823 by the Rurik and the Apollon, and the 1824 visits by the Ladoga and Kreiser, caused concern with the colony authorities, who reported their concerns to London. In 1825 and 1928, the Elena visited Australia followed by the Krotky in 1829, the Amerika in 1831 and 1835. Visits by Russian ships became so common in Sydney Cove, that their place of mooring near Neutral Bay became known as Russian Point, and added to the sense of alarm in the Colonies.[3][6] By the late-1830s, relations between Russia and Britain had deteriorated, and in 1841 the Government of New South Wales decided to establish fortification at

Pinchgut in order to repel a feared Russian invasion.[7][8] Fortifications at Queenscliff, Portsea, and Mud Islands in Melbourne's Port Philip Bay followed, as did similar structures on the Tamar River near Launceston and

on the banks of the Derwent River at Sandy Bay and Hobart.

As Australia was engaged in a gold rush in the 1840s and 1850, in conjunction with the Crimean War between England and Russia, paranoia of a Russian invasion gripped the Colony, and Russophobia increased. In 1855,

the Colony built fortifications around Admiralty House and completed Fort Denison on Pinchgut Island, as the emergence of the Pacific Ocean Fleet of the Imperial Russian Navy furthered the fear of a Russian invasion of the

Colonies, and rumours spread that the Russians had invaded the Port of Melbourne.[6][7][9][10]

Inflows of Russians and Russian-speaking immigrants which began to increase in the 1850s, and the nature of friendly relations between Russian and Australian representatives, led to the appointment of two Russian honorary

consuls in 1857; James Damyon in Melbourne and EM Paul in Sydney.[9][1][2]

Seven years after the conclusion of the Crimean War, the Russian corvette, and flagship of the Russian Pacific squadron, Bogatyr visited Melbourne and Sydney in 1863. The corvette visited the cities on a navigational drill

under the Commander of the Russian Pacific Fleet Read Admiral Andrey Alexandrovich Popov, and the ship and crew were welcomed with warmth. Popov paid Governor of Victoria Henry Barkly and Governor of New

South Wales John Young protocol visits, and they in turn visited the Russian ship. The Russians opened the ship for public visitation in Melbourne, and more than 8,000 Australians visited the ship over a period of several days. The

goodwill visit was a success, however, the Bogatyr's appearance in Melbourne did put the city on a war footing, as noted in The Argus which reported that the ship managed to approach Melbourne unnoticed, ostensibly due to the lack of naval forces in Port Phillip Bay. After the Bogatyr had left the Colony, the Sydney Morning Herald reported on 7 April 1863 that the crew of the ship had engaged in topographical surveys of the Port Jackson and Botany Bay

areas, which included investigating coastal fortifications, but this didn't raise any eyebrows at the time[11][10]

Anti-Russian sentiment began to take hold in the Australian media in November 1864 after the publication by The Times in London of an article which asserted that the Colonies were on the edge of a Russian invasion. The

article published on 17 September 1864 stated that Rear Admiral Popov received instructions from the Russian Naval Minister to raid Melbourne in the event there was a Russo-English war, but noted that such a plan was

unlikely due to its perception of the Russian forces being inadequate for such an attack. Australian newspapers, including The Age and Argus took The Times' claims more seriously and began to write on the need to increase

defence capabilities to protect against the threat of a Russian invasion.[11]

On 11 May 1870, rumours spread in Hobart that a Russian invasion was almost a certainty, with the rumours being

based upon the appearance of the corvette Boyarin at the Derwent River. The reason for the appearance of the Russian warship was humanitarian in nature; the ship's purser was ill and Captain Serkov gained permission to

hospitalise Grigory Belavin and remain in port for two weeks to replenish supplies and give the crew opportunity for some shore leave. The ships officers were guests at the Governor's Ball held in honour of the birthday of Queen

Victoria, and The Mercury noted that the officers were gallant and spoke three languages including English and French. The following date a parade was held, and the crew of the Boyarin raised the Union Jack on its mast and

fired a 21-gun salute in honour to the British queen. This was reciprocated by the town garrison which raised the Russian Naval flag of Saint Andrew and firing a salute in honour of Tsar Alexander II. After the death of Belavin,

permission was given to bury him on shore, and his funeral saw the attendance of thousands of Hobart residents, and the locals donated funds to provide for a headstone on his grave. In gratitude of the welcome and care given by the Hobart citizenry, Captain Serkov presented the City of Hobart with two mortars from the ship, which still stand today at the entrance to the Anglesea Barracks. When the Boyarin left Hobart on 12 June, a military band onshore played God Save the Tsar, and the ship's crew replied by playing God Save the Queen.[12]

Although the visits of Russian ships were of a friendly nature, the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878 was seen by Britain to be part of a potential expansion plan by the Russian Empire into India, and the Australian Colonies

were advised to upgrade their defence capabilities. The inadequacy of defences in the colony was seen in 1862, when the Svetlana sailed into Port Phillip Bay and the fort built had no gunpowder for its cannons to use to return a salute. William Jervois, a Royal Engineer, was commissioned to determine the defence capabilities of all colonies, with the exception of Western Australia. In his report, he was convinced that the Russian Empire would to attack South Australian shipping in an attempt to destroy the local economy. As a result of Jervois' report, Fort Glanville

and Fort Largs being built to protect Port Adelaide.[13][7][14]

The "Russian threat" and Russophobia continued to permeate in Australian society, and was instrumental in the decision to build Australia's first true warships, the HMS Acheron and HMS Avernus, in 1879.[15]

The Melbourne-based Epoch re-ignited fears of a Russia invasion when three Russian ships; the Afrika, Vestnik, and Platon were sighted near Port Philip in January 1882. Despite the hysteria generated by the media in Melbourne, no invasion ensued. David Syme, the proprietor of The Age wrote in a series of editorials that the visit of the three ships was associated with a war that was threatening to engulf Britain and Russia, and that the squadron

under the command of Avraamy Aslanbegov was in the Pacific in order to raid British commerce. Newspapers wrote that Admiral Aslanbegov behaved like a varnished barbarian due to his non-acceptance of invitations, and because he preferred to stay at the Menzies Hotel, rather than the Melbourne Club or the Australian Club.

Aslanbegov was accused of spying and fraud, leading to the Admiral complaining to the Premier of Victoria Bryan

O'Loghlen and threatening legal action against the newspaper. John Wodehouse, 1st Earl of Kimberley, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, defused the situation when he sent a telegraph to the government stating that relations with Russia are of a friendly character, and such newspaper reports are rendered incredible.[13] Due to the fears of an invasion, Fort Scratchley in Newcastle was completed by 1885.[7]

Nicholai Miklukho-Maklai after conducting ethnographic research in New Guinea since 1871 moved to the Australian Colonies in 1878, where he worked on William John Macleay's zoological collection in Sydney and set up Australia's first biological marine station in 1881.[1]

Since 1883 he advocated setting up a Russian protectorate on the Maclay Coast in New Guinea, and noted his ideas of Russian expansionism in letters to those in power in Saint Petersburg. In a letter he wrote to N. V. Kopylov in 1883, he noted there was a mood of expansionism in Australia, particularly towards New Guinea and the islands in Oceania. He also wrote to Tsar Alexander III in December 1883, the letter in which he suggested that due to the lack of a Russian sphere of influence in the South Pacific and English domination in the region, there was a threat to Russian supremacy in the North Pacific.

This view was mirrored in a letter to Konstantin Pobedonostsev, and he expressed his willingness to provide assistance in pursuing Russian interests in the region. Nicholas de Giers, the Russian Foreign Minister suggested in reports to the Tsar that relations with Miklukho-Maklai should be maintain due to his familiarity of political and

military issues in the region, whilst not advising him of any plans on the Government's plans for the region. This opinion was mirrored by the Naval Ministry. In total, three reports were sent to Russia by Miklukho-Maklai, containing information on the growth of anti-Russian sentiment and the buildup of the military in Australia, which correlated with the worsening of Anglo-Russian relations.

Noting the establishment of coal bunkers and the fortifying of ports in Sydney, Melbourne, and Adelaide, he advocated taking over Port Darwin, Thursday Island, Newcastle, and Albany, noting their insufficient fortification. The Foreign Ministry considered a Russian colony in the Pacific as unlikely and military notes of the reports were

only partially utilised by the Naval Ministry. The authorities in Russia appraised his reports, and in December 1886 de Giers officially advised Miklukho-Maklai that his request for the establishment of a Russian colony had been

declined.[16][7]

1888-1917

The Russian corvette Rynda in Sydney in 1888.

Paranoia of a Russian invasion subsided in 1888, when Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich arrived in the Colony onboard the corvette Rynda as part of celebrations of the Colonial bicentenary. Rynda pulled into Newcastle in the afternoon of 19 January 1888 to replenish coal supplies, becoming the first Russian naval visitor to the city.[17][7]

The Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate reported on 20 January 1888 that given the uncertain state

of diplomatic relations between the European powers many people fled fearing that the Russian warship was present in Newcastle to start a war; however, those fears were quickly allayed when the goodwill nature of the visit became known.[18]

From Newcastle, Rynda sailed to Sydney.The day after arrival Lord Carrington, the Governor of New South Wales,

sent a coach to bring the Grand Duke to Government House. He was unable to attend due to laws of the Russian Empire which prohibited participation in State ceremonies of foreign states. The Russian officers attended Government House on 24 January as the guest of Lady Carrington. HMS Nelson was late arriving in Sydney and on 26 January, the day of celebrations, the Rynda orchestra was invited to entertain the public, and the Australian

media made the Grand Duke the central focus of the events.

On 30 January the Russian officers were present at the ceremony of the foundation of the new parliament building. One hundred seamen from Rynda were invited to a festival organised by the citizens of Sydney on 31 January, and the Russian and French flags were given prominence next to the Australian flag, whilst those of other nations were along the walls. Denoting the goodwill nature of the visit, Lord Carrington in a speech said, "We welcome into the

waters of Port Jackson the gallant ship Rynda, we welcome the gallant sailors who sail under the blue cross of Saint Andrew, and we especially welcome - though we are not permitted to do so in official manner - that distinguished officer who is on board, a close blood-relation of his Majesty the Tsar. Though not permitted to offer him an official welcome, we offer him a right royal welcome with all our hearts."

Rynda left Sydney on 9 February and arrived in Melbourne on 12 February. The visit was initially reported positively in the press and after a few days The Age began to campaign for the restriction of the entry foreign naval ships into Melbourne, and other articles described the expected war between "semi-barbarous and despotic Russia" and England.

The public, however, continued to view the presence of the Russians positively, and on 22 February the Mayor of Melbourne Benjamin Benjamin visited the ships. After staying for nearly a month, Rynda left Melbourne on 6 March for New Zealand.[19] The Grand Duke supported expanding trade ties with Australia, noting that it was desirable for the Russians to expand their ties with Australia, outside of their relationship with Britain, and stated his belief that such relations were long overdue.[1]

In 1890, the Government in Saint Petersburg concluded Anglo-Russian relations in the Pacific to have reached a level whereby it was decided to appoint a career diplomat to represent Russian interests in the Australian Colonies. When John Jamison, the honorary consul in Melbourne, went bankrupt and was no longer able to represent Russia's interests, the Russian government appointed Alexey Poutyata as the first Imperial Russian Consul to the Colonies on 14 July 1893, and he arrived with his family in Melbourne on 13 December 1893. Poutyata was an effective Consul and his reports were well read in Saint Petersburg.[20] His efforts at encouraging Australian manufacturers and merchants to attend the All-Russia Exhibition 1896 in Nizhny Novgorod were instrumental in the signing of

commercial contracts between Tasmanian merchants and manufacturers in Russia. Poutyata died of kidney failure following complications from pneumonia a little over a year after his arrival in Australia on 16 December 1894, which saw Robert Ungern von Sternberg being appointed to replace him at the end of 1895.[21][1][22]

Nikolai Matyunin, who replaced Sternberg as Consul in 1898, signed an agreement with Dalgety Australia Ltd, which enabled Russian cargo ships to carry the company's pastoral products back to Europe.[1]?

The opening of the Australian Parliament on 9 May 1901 at which the Russian Empire was represented by Nicolai Passek, the Imperial Consul in Melbourne.

In 1900, the Imperial Ministry of Foreign Affairs was advised that the Duke and Duchess of York would be visiting Australia for the opening of the Australian Federal Parliament in 1901, whereupon it was viewed as necessary to send a Russian naval vessel, and the Gromoboi, captained by Karl Jessen was ordered to divert to Melbourne on 24 February [O.S. 12 February] 1901.

On 1 March [O.S. 19 February] 1901, the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Vladimir Lambsdorff wrote to the Naval Minister, advising him that sending a ship was not a political act but one of diplomatic etiquette. Tsar Nicholas II viewed that "(i)t is desirable to send a cruiser". The Gromoboi arrived in Melbourne, after a call in Albany in the Great Southern region of Western Australia, on 30 April 1901. The Russian Empire was represented at the opening of the first Australian Parliament on 1 May 1901 by Russian consul Nicolai Passek, who was based in Melbourne since the approval of his appointment by Queen Victoria on 24 March 1900.[23][1][24]

The Duke of York visited the Gromoboi and was impressed by the cruiser, and he sent a request to Tsar Nicholas II asking that Jessen and the Gromoboi be allowed to accompany him to Sydney as an honour escort; a request which was approved.[23]

British financial and political support for the Japanese during the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 - 1905 caused disagreement with the British foreign policy in Australia. The authorities in Australia were concerned that the Japanese military posed a threat to the national security of the country, and the fear existed even when Japan was an ally of the Entente Powers in World War I. During the war, as a member of the British Empire, Australia was allied with Russia, and this alliance led to the Russians, in late 1914 requesting a military operation which could turn

Ottoman troops away from the Caucasian Front and open up the Dardanelles, so that cargo ships could bring military supplies to Russia's ports on the Black Sea. The Campaign at Gallipoli was disastrous for the British-led

military, and was instrumental in Russian defeats in the summer of 1915.

References

1. a b c d e f g h i j k "60th Anniversary of the Russian-Australian diplomatic relations". Embassy of Russia to Australia.

Retrieved 2009-04-06.

Archived at WebCite

2. a b c d e Parliamentary Debates, New South Wales

Legislative Council, 13

June 2002, page 3153

3. a b c d Protopopov, A Russian Presence: A History of

the Russian Church

in Australia, p. 1

4. "The Sloop Neva, the first Russian ship to visit

Australia". Naval

Historical Society of Australia. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

5. Govor, Elena (1999). "?????????? ?????? ??????? ?

??????? (Governor

Lachlan Macquarie and Russians)". Avstraliada (9): 1-4.

Retrieved

2009-04-07.

6. a b c Protopopov, A Russian Presence: A History of the

Russian Church in

Australia, p. 2

7. a b c d e f Scanlon, Mike (19 July 2008). "Unorthodox

Russians". The

Newcastle Herald.

8. a b c Kroupnik, Vladimir. "Russia and Australia - Two

Centuries".

Russia-Australia Historical Military Connections.

Retrieved 2009-04-06.

9. a b c Govor, Elena (1988). Graeme Davison. ed. Oxford

Companion to

Australian History. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

pp. 567-568. ISBN

0195535979.

10. a b Protopopov, A Russian Presence: A History of the

Russian Church in

Australia, p. 3

11. a b Massov, Alexander. "The Russian corvette "Bogatyr"

in Melbourne and

Sydney in 1863.". Russia-Australia Historical Military

Connections.

Retrieved 2009-04-06.

12. Protopopov, A Russian Presence: A History of the

Russian Church in

Australia, p. 7

13. a b Protopopov, A Russian Presence: A History of the

Russian Church in

Australia, p. 8

14. Kroupnik, Vladimir. "The frigate "Svetlana" in

Australia in 1862".

Russia-Australia Historical Military Connections.

Retrieved 2009-04-09.

15. Gillett, Ross. "Australia's First Warship - The

Torpedo Boat Acheron".

Naval Historical Society of Australia. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

16. Massov, Alexander. "Nikolai Nikolaevich

Miklouho-Maclay at the service

of his Motherland". Russia-Australia Historical Military

Connections.

Retrieved 2009-04-08.

17. "The Russian Corvette Rynda". Brisbane Courier. 27

January 1888. pp. 7.

Retrieved 2009-04-07.

18. Other, A. N.. "HIRMS Rynda Arrives". Naval Historical

Society of

Australia. Retrieved 2009-04-07.

19. Govor, Elena; Massov, Alexander (1988). ""Rynda" v

gostiakh u

avstraliitsev (k 110-letiyu vizita v Avstraliyu)".

Avstraliada. Retrieved

2009-04-09.

20. Protopopov, A Russian Presence: A History of the

Russian Church in

Australia, p. 10 Church in Australia, p. 15

21. (Russian) Govor, Elena. "????????? ? ??????? ???????".

?????????????

???????. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

22. a b Massov, Alexander. "Diplomatic mission of the

"Gromoboy" cruiser".

Russia-Australia Historical Military Connections.

Retrieved 2009-04-11.

23. "Foreign Office, March 24, 1900.". The London Gazette.

6 April 1900.

Retrieved 2009-04-11.

In 1997 Mrs N. Melnikova, the editor of Australiada, a

magazine for Russian Australians with a strong

commitment to the Orthodox Church, published an

editorial which accurately placed Father Dionysius'

service on board Vostok, not in Sydney but off the coast

of New South Wales. Melnikova also sensibly revised the

traditional claim from 'first service' to 'first

Easter', since even if we discount ship visits in

previous years it can safely be assumed that Father

Ivanov, on the other expedition that year, celebrated

many of the liturgies of Great Lent and Holy Week in

Port Jackson between 2 March and 5 April 1820.

BTW I have written to Father Protopopov. No reply.

If I didn't think you had a great website I wouldn't be writing this, so don't take it the wrong way if I point out a few problems with this otherwise valuable article: Early Visits of Russian Warships to Australia.

The first thing about 1820 is to get the expeditions

sorted out. There were two separate expeditions with two

ships each and they made separate visits to Sydney which

did not overlap.

What the Russians called the 'second', northern

expedition was commanded by Vasiliev. They reached

Sydney first, on 2 March 1820, and left on 6 April.

The 'first' or southern expedition was commanded by

Bellingshausen (NOT Lazarev please, however popular his

previous visit had made him). B. reached Sydney with

Vostok on 11 April. Lazarev followed with Mirnyi on 19

April. They left together on 19 May.

All this is in Governor Macquarie's diaries and

confirmed by the Sydney Gazette. Also Cumpston as far as

I recall.

What is not in any of those sources is the fairy-tale

about celebrating the Orthodox Easter on board Vostok,

and for very good reason:

So there you are, no Australian guests, no wooded

shores reverberating to the Russian choir etc. etc.

All just so much balderdash put into circulation by

a certain Mr Melnikov in 1997, apparently. Goodness

knows why, since he was obviously well able to read

B's book for himself and the libraries of Sydney

doubtless have the odd copy!

Doubtless also, however, services were held during

the northern squadron's visit in March, and if none

of the previous Russian ships held any, they would

have been the first in Australia. But obviously

Vasiliev was not a glamorous enough celebrity for

some people. So they have fabricated the

Bellingshausen Easter myth instead.

As a graduate of Adelaide Uni and a historian hugely

beholden to your libraries and archives, I really

dislike seeing one of my favourite countries being sold

a pup like this one. So if you can do anything at all to

spread some of these points around the maritime history

community, I would be most grateful.

Dr R. I. P. Bulkeley

Oxford

U. K.